Designed by London-based practice, Amos Goldreich Architecture, alongside local firm, Jacobs-Yaniv Architects, this shelter is one of only a handful in the world which has been designed and built in consultation with the staff who will occupy and run it. Led by pioneering human rights activist, Ruth Rasnic, for international charity ‘No To Violence’, the facility will provide a much-needed refuge for distressed and abused women and children from all localities and backgrounds.

According to World Health Organisation data up to 45% of women in Israel, like most countries in the west, will be victims of domestic violence at some stage in their lives and recent statistics indicate that 45% of children in Israel are subjected to violence. This is a worldwide epidemic.

“My family wanted to create something worthwhile in memory of my late grandmother Ada, a feminist who was involved in many charities in Israel,” says Amos Goldreich, Director of Amos Goldreich Architecture. “They approached Ruth Rasnic, a childhood friend of my late mother, who founded the charity 'No To Violence' in 1977, in order to raise public awareness about domestic abuse in Israel, as well as provide support for victims. That is how the project started.”

The charity currently operates three shelters, and whilst it foots 60% of ongoing expenses, the government does not assist with building expenditure.

This will be the charity’s first purpose-built shelter, as well as accommodating its administrative headquarters, and has been designed to house families from diverse ethnic and geographical backgrounds, including Arab, Israeli, Ethiopian, Russian and Ukrainian women and children.

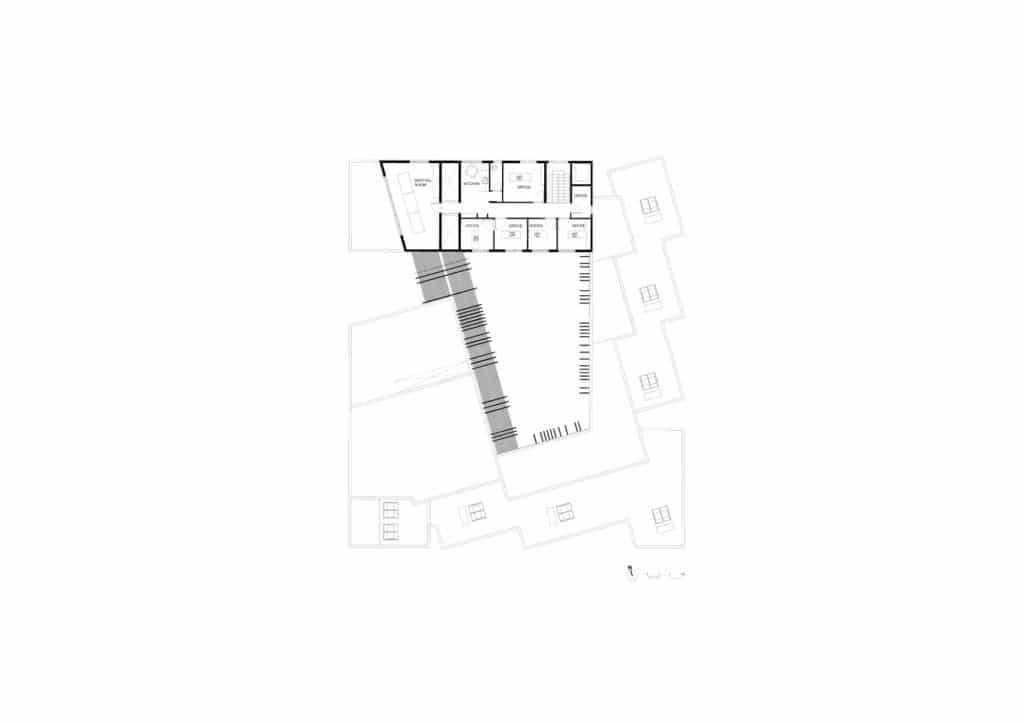

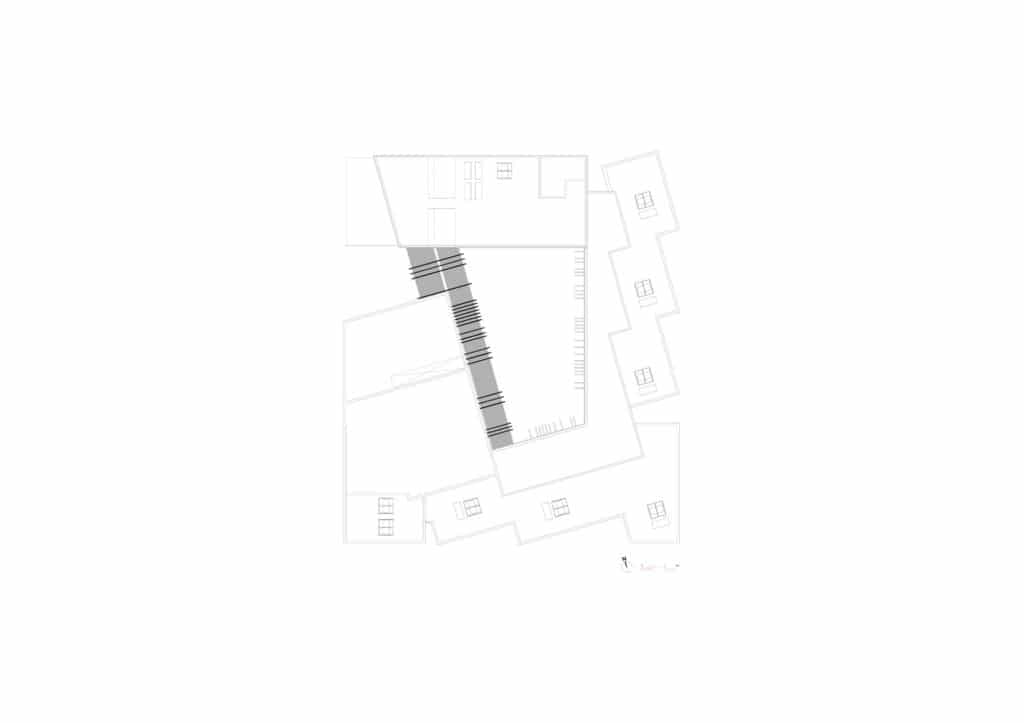

The site for the shelter measures 1600 square metres, is located within a quiet residential neighbourhood and surrounded by a mix of private residential houses and blocks of flats. The brief specified a location within reach of local community resources, i.e. stores, jobs, health clinics, schools, parks and other green spaces, counselling centres and recreational facilities.

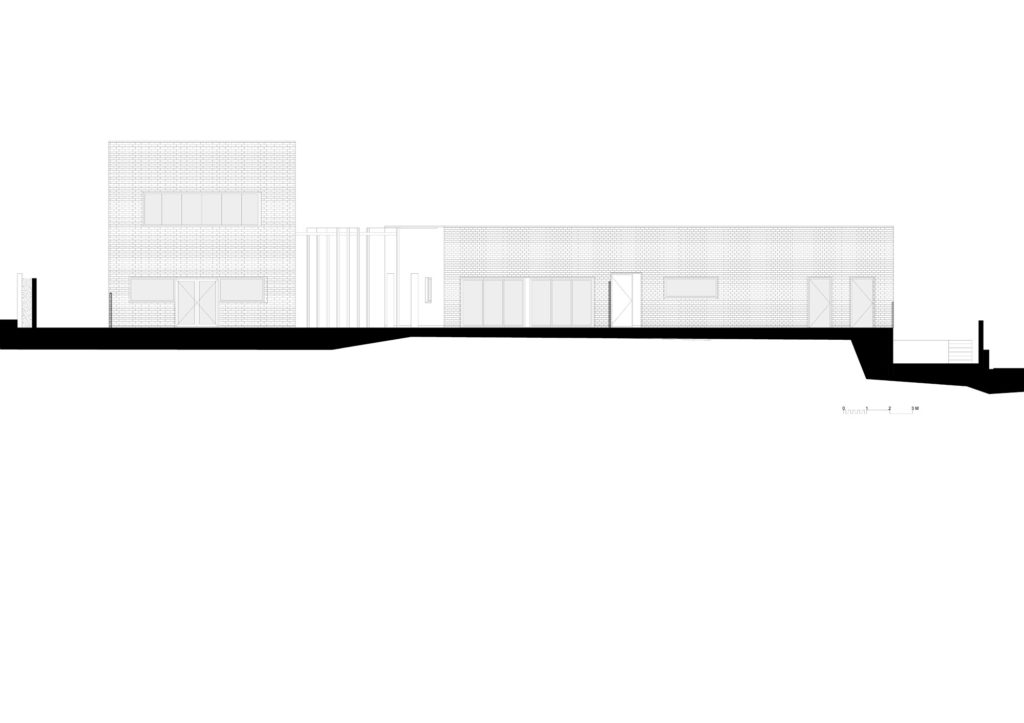

The new shelter replaces an existing one in the same city which was established 37 years ago. The majority of existing shelters in Israel are not purpose-built. Located in converted buildings, they are overcrowded, with too many stairs and blind areas, compromising the safety of the residents. The new brief thus called for a totally secure and sheltered building - a peaceful haven that would give its inhabitants a sense of home.

The site was provided by the local municipality, but this proved a challenge, as local neighbours objected to it. Numerous consultations with neighbours and the municipality took place, including reviews of the residents' legal objections to the scheme by the High Court which went on for six years, before it ruled in favour of the shelter.

We were two briefs: one was set out by the Ministry of Social Affairs, the other, which complemented it, by the charity. The charity was very involved in the development of the brief and the design discussions, stipulating that the shelter needed to accommodate up to twelve families, all of whom require individual privacy, yet need to coexist with each other and with the staff who look after them. Each family has three children on average, so the design of the building was predicated on a floating population of more than 24 residents at any one time.

Another paramount request was to create a sense of home and security for the inhabitants, without it feeling like a prison. For safety reasons, residents spend most of their day in the shelter, and so the major design challenge was how to accommodate all families in a peaceful manner for extended periods of time.

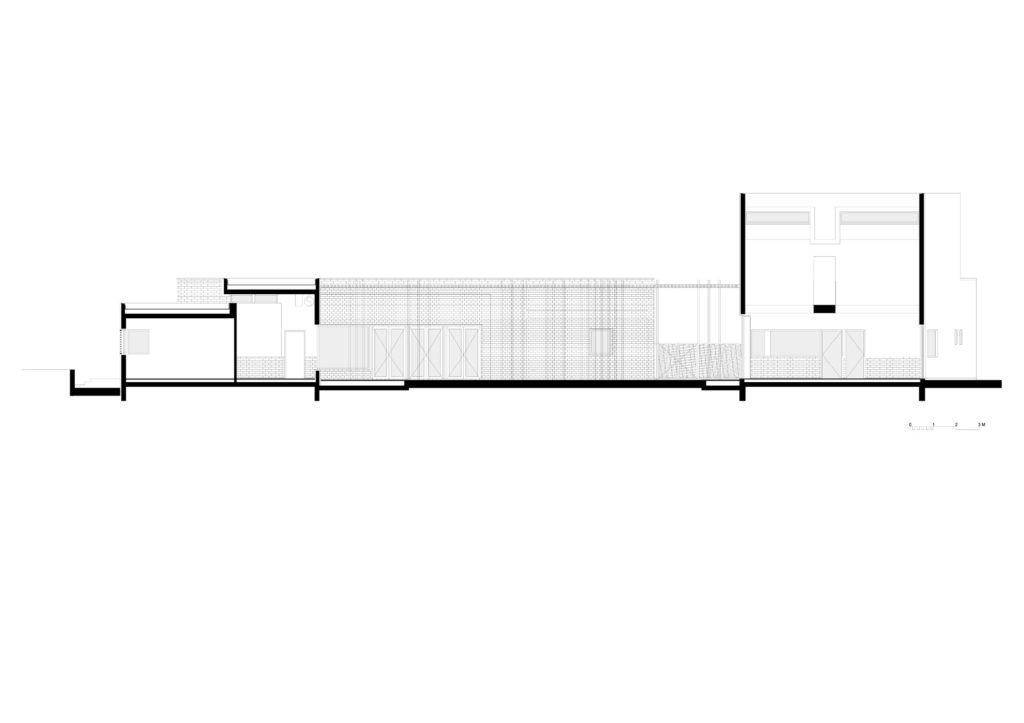

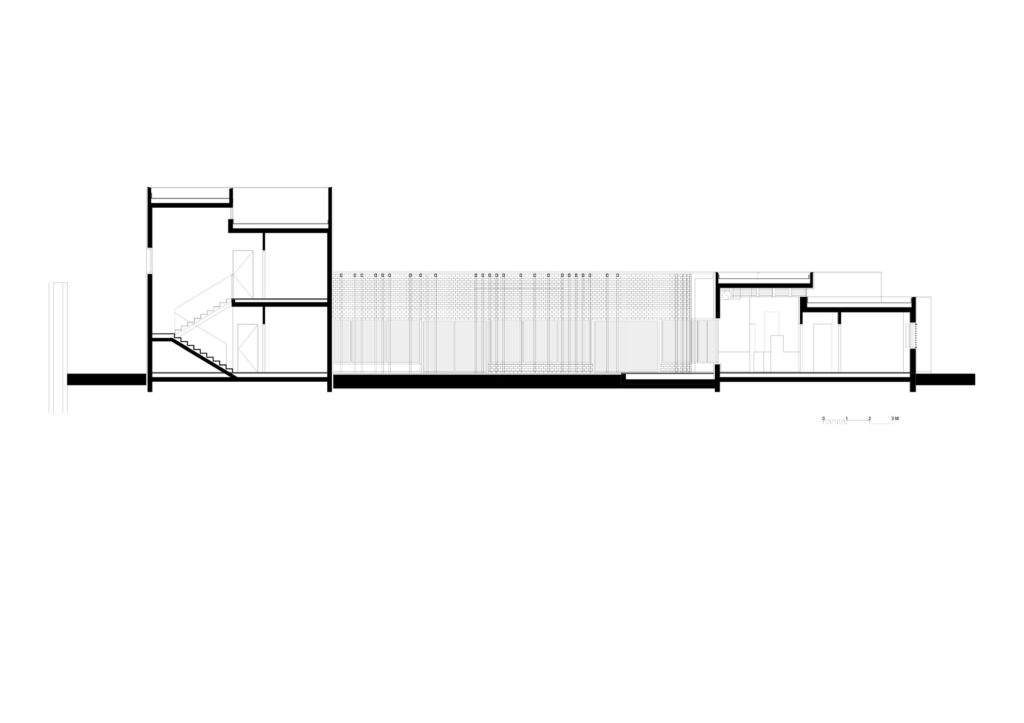

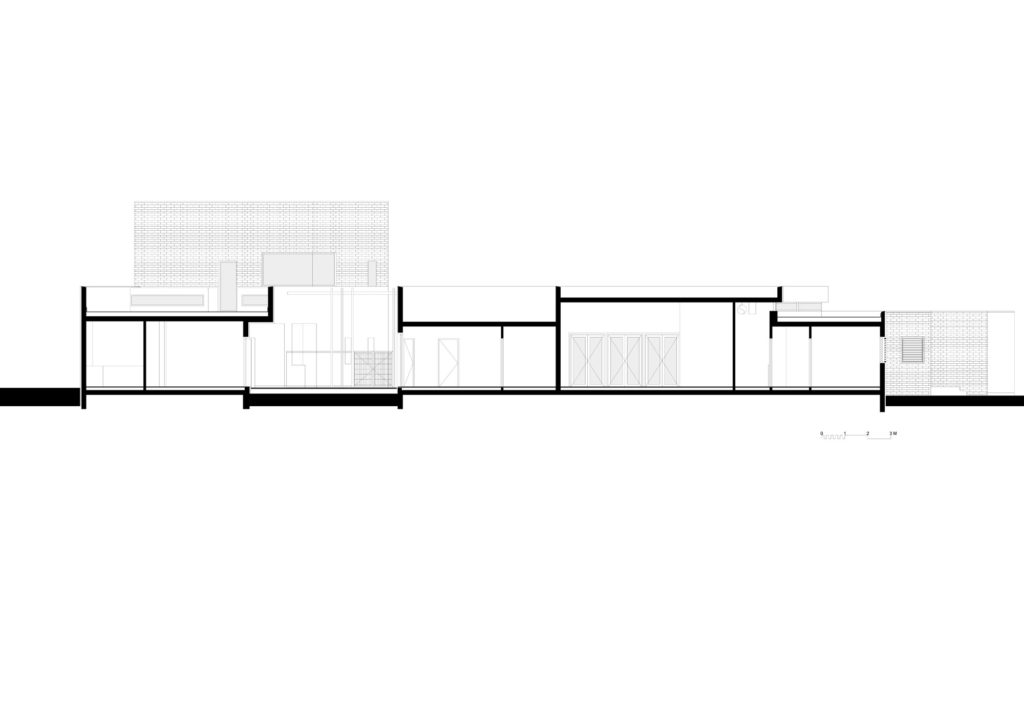

The building has two facades - the secure and protective exterior, and the inner façade, giving onto the central garden, the therapeutic “heart” of the shelter.”

On arrival at the shelter, each new family is given a small ‘house’ that is part of the larger building. In order to allow the families to conduct a normal daily routine in the shelter, the ‘houses’ are separated from the communal functions and connected by the internal corridor. The nursery is physically separated from the larger building, which allows it to function as an ordinary nursery would, allowing women to drop their children off in the mornings, and collect them later in the day.

The green sanctum of the inner courtyard plays a crucial role as a meeting place for the residents. It also serves a functional purpose, providing optimum visual connections between the house mother and the families, as well as between the women and their children. The surrounding internal corridor (or ‘street’) connects the inside and outdoor spaces and creates a free-flowing space in which women and children can interact, while at the same time maintaining mutual sight lines between them and the staff.

comments